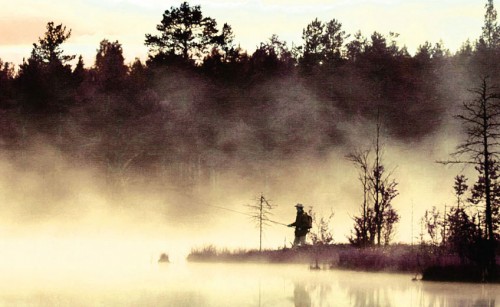

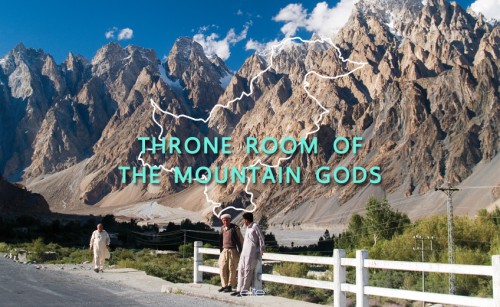

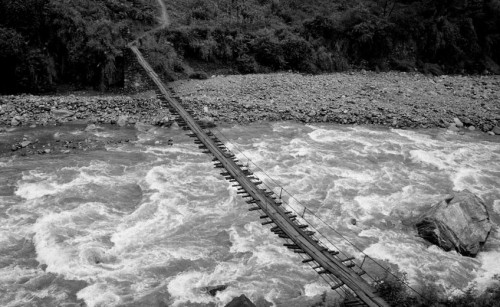

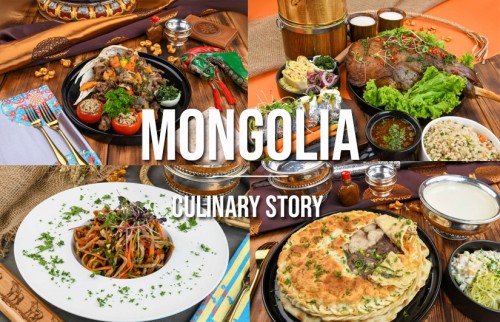

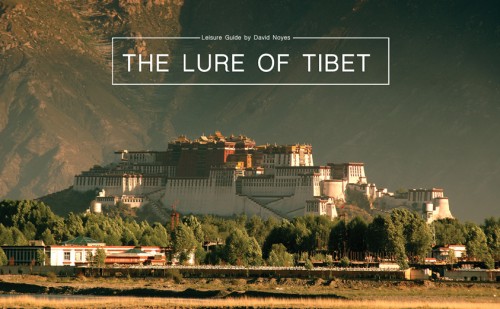

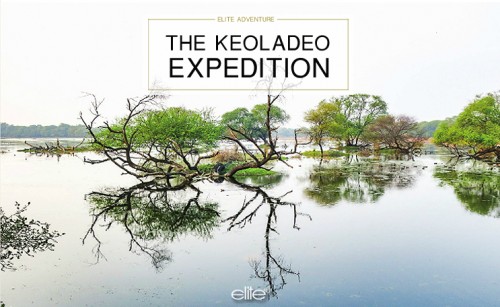

Bounded by the Altai Mountains and grassy steppes of Mongolia, the vast Gobi Desert is entrenched in iconic images of Marco Polo’s Silk Road and the yore of Genghis Khan. It may sound enchanting, but the realities of the Gobi are quite different. Temperature extremes, ranging from -40C in the winter to 45C in the summer, make it one of the more inhospitable climates on the planet, and the limited access to water, bumpy sand tracks that serve as roads and minute population ensure that if travellers don’t come in prepared, they might not be MONGOLIA’S GOBI DESERT The stunning colours and sounds of one of the most inhospitable places on Earth coming back out. (In fact, the western border of the Gobi, the Taklamakan Desert, is named from the Uighur language and means “you can get in, but you cannot get out”.) However severe it might sound, this hasn’t stopped explorers and adventurers from heading out to the blistering sands of the Gobi, and I recently spent time travelling through its more accessible reaches, hiring an old Russian Furgon van and driver to get me out to the most scenic parts.

While the Gobi is actually mostly scrub desert, it has one section, known as Khongoryn Els, or the “singing sand dunes” (named for the sounds the sands make when wind blows through the dunes), which is simply epic. Located in the middle of Gobi Gurvansaikhan National Park, huge 300-metre-high Saharan-style dunes rise from the desert here, their contours and folds changing colour and light throughout the day. Visitors normally ride camels to access their slopes, but I headed off on my own, gasping for breath in the arid bone-dry air as I sunk up to my knees with every step, labouring up to the top of the highest dune just before the sun turned to a soft gold and retreated over the horizon.

The desert may appear lifeless to some, but linger a bit and and it comes to life. Besides the captivating wild Bactrian camels that wander freely here, there are golden eagles, ibex, Mongolian wild ass, pit vipers and even bears and the elusive snow leopard to be found in its furthest reaches.

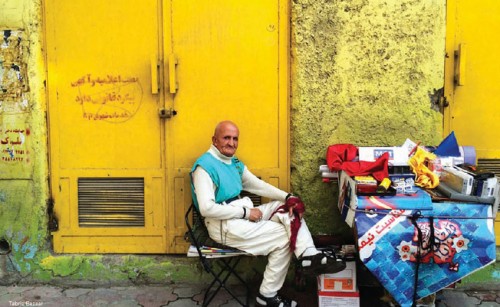

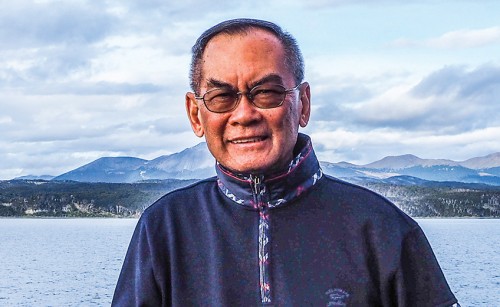

Human habitation is sparse out here, but the nomadic herders who do eke out a living in the extreme climate are very welcoming. Mongolian ger (yurt) encampments are found scattered throughout the dune areas, and long-standing tradition dictates that travellers be warmly welcomed from the rigours of the desert. I spent several nights sleeping warm and cosy inside a ger, heated by a stove burning camel dung, and being served fresh camel milk by a pair of weathered septuagenarians who had lived out here their entire lives. We communicated mostly via hand signals, but the old man signalled that we must be the same, as he pointed to his bald head, and ran his hand over my receding pate with mirth, laughing aloud all the while.

The next morning I woke up at dawn to go out and take some photos. The air was completely still except for the rustling of several camels wandering into the grass fronting the nearby dunes. Suddenly out of nowhere, the wind picked up and I heard voices. They became louder, reaching a crescendo after 10 minutes that was almost frightening. I thought for a minute I could hear an aeroplane approaching, and then it hit me that this was the sand, the “singing” dunes I had heard so much about. They say the sound created by sand movement can rise to over 100 decibels, equivalent to an outboard motor starting up or live rock concert! A minute later the cacophony had passed, and once again I had the silent desert to myself, with a magnificent array of oranges and ambers spread out before me

.jpg)